Doing research interviews during the pandemic

CDE member, Ryan Swift, writes about his experience of undertaking interviews at a time of pandemic and how, interestingly, in some ways the online interview opens up new possibilities, rather than restricting these.

My PhD research looks at the North of England within contemporary political debate. It is interested in the ways in which and the extent to which the North is framed and politicised and the implications of this on policy debates and political action. To gain insights into these issues, I have undertaken qualitative interviews with key actors important to ongoing political discourse on the North including elected national and local politicians from a variety of parties as well as political advisors, civil servants, and representatives from interest groups, think tanks, and the media.

Arranging and conducting elite interviews can be difficult at the best of times, but the coronavirus pandemic has brought further challenges for those undertaking this kind of primary research. In total I have conducted 74 interviews for this research project, 47 of which were carried out after the first national lockdown came into force in March 2020. In this blog post I reflect on two of the main challenges I have faced in pursuing this research during the pandemic. The first is on the issue of getting the interview and the challenges of unresponsiveness or declinations from potential interview participants. The second is on the issue of conducting the interview, in particular the use of alternative mediums of doing so other than the face-to-face meeting.

Getting the interview

The sampling method that I used for this research was purposive with potential participants being identified based on their relevance and contribution to the current debates about the politics of the North. I sought to ensure that the final sample was as diverse as possible by seeking to recruit participants from different arenas and professional positions, trying to make sure that the contrasting perspectives and arguments of the different sides of the debates on the North were heard, and through making attempts to ensure that it was demographically and geographically representative.

One of the main challenges the researcher faces in seeking a strong and diverse interview sample is that inevitably many potential participants identified in the target sample will not want to or be able to take part in the study. This was the case in my research where plenty of potential participants declined an interview for various reasons, while many others did not respond to requests to take part at all. But the challenge of getting the interview was made even stiffer by the arrival of COVID-19. Many already extremely busy potential participants found their workload increased further, this was particularly so for MPs, councillors, civil servants, and journalists. As such, it became increasingly common to receive responses declining invites to participate in the study citing a lack of time due to the pandemic.

To overcome, or at least mitigate this issue, several steps were taken. First, I approached many more potential participants from all categories in the target sample than I sought to interview. This ensured that, even accounting for non-responses and declinations, there was at least some representation for each category. Second, all potential participants were re-contacted up to a maximum of three times if they did not respond to requests to take part. This was useful as it was quite common to receive positive responses at the second or even third time of asking. Perhaps because earlier requests had simply been overlooked or maybe because participants’ circumstances had changed at the time of the subsequent request.

Conducting the interview

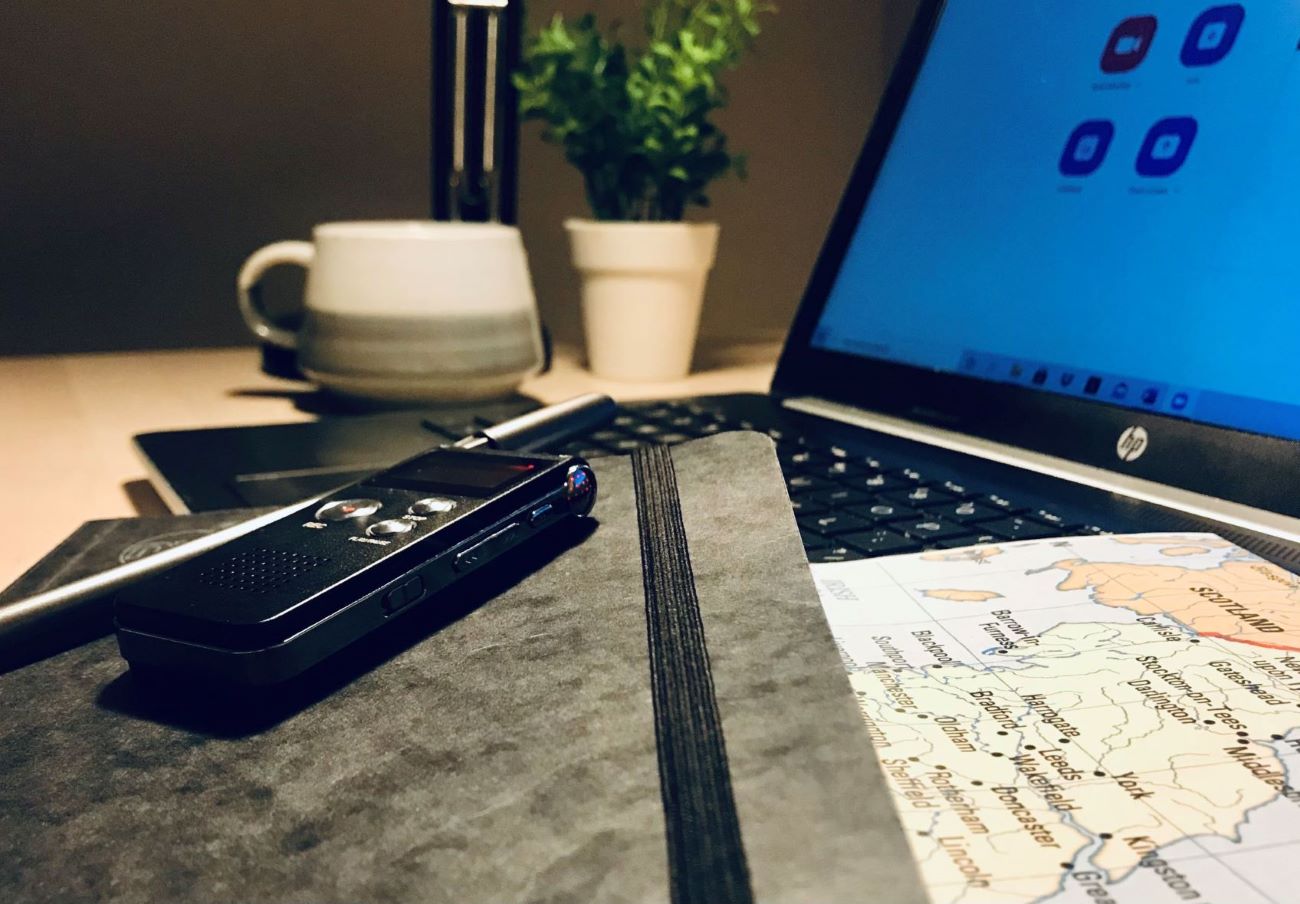

The second, and the more unprecedented, challenge I faced in my research was that as a result of the pandemic the majority of interviews were done via online video call. Most of the earlier interviews that I carried out before the pandemic hit had been conducted face-to-face, and all throughout the data collection process telephone interviews were conducted on occasion when this was the preference of the interview participant. The use of these different mediums for conducting the research interviews presented some difficulties but also provided benefits and enabled some interesting insights to be gleaned concerning the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Within the methods literature on interviewing, face-to-face interviews are often seen to be the ‘gold standard’, but it is increasingly recognised that different modes of conducting the interview can be used with success. In my experience, I found few discernible drawbacks of online video interviews compared to face-to-face interviews and found that they can instead provide a number of advantages both for the researcher and the interview participant. For a start, online video calls can provide benefits in terms of convenience. The researcher and interviewees can participate from a location of their choosing, significant time and expense can be saved in not having to travel to meet participants face-to-face, and it means that more than one interview with participants in different locations can be conducted in a day.

In terms of the dynamics of online video call interviews, I found that it was still possible to experience the benefits of face-to-face interviewing such as rapport building and responding to the visual cues of the participants. The only drawbacks were the occasional connection issues, and it did appear that participants were more likely to request to rearrange video call interviews than face-to-face interviews, but this was not a problem because no time or expense was lost.

Much of the above is also true of telephone interviews although, in my experience, they can present a few additional drawbacks primarily associated with the lack of visual cues. Unlike face-to-face and video call interviews it was sometimes more difficult to pick up on participants sentiments without the addition of facial expressions or hand gestures. It was also sometimes hard to gage whether participants had finished answering a question or had just taken a pause, this presented extra challenges around interrupting participants to ask additional probing questions or to determine when to move on to another line of questioning. That said, these issues did not significantly harm the dynamics of the interview and all of the telephone interviews I conducted did provide many useful insights.

Given the circumstances and the restrictions in place for most of my study’s data collection period, utilising alternatives to the face-to-face interview was unavoidable. This did, however, highlight that alternative mediums, in particular the online video call, have many positives and are perhaps likely to continue to be employed by researchers as we move forwards.