Diversity, the Authoritarian Predisposition, and Political Participation

Immigration is continuing to drive political agendas around the world. In Australia, parliament recently approved a bill to allow some asylum seekers into the country on medical grounds reigniting debates over immigration and asylum seekers. Europe continues to struggle with the political and social fallout from the recent inflow of hundreds of thousands of refugees from the Middle East and Northern Africa. In the United States, President Trump continues with his goal to build a wall along the border with Mexico, doubling down on his campaign rhetoric about the evils of immigration from Mexico and going so far as to declare a state of emergency in order to side-step Congress. Even the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the E.U., a political, social, and economic change of immense proportions, is being partially attributed to negative views of immigration.

The resulting upward trends in socio-ethnic diversity due to continuing or increased immigration have a wide range of social, economic, and political effects. In an article we published in the European Journal of Political Research, we look at how such diversity shapes political participation. An earlier body of literature indicates that diversity decreases participation for two reasons. First, heterogeneous communities have lower levels of intergroup social interaction which decreases social capital. Lower social capital, in turn, decreases people’s willingness to participate in wider social and political activity. Second, the presence of “others” produces anxiety that arises from potential competition over economic resources and/or cultural norms. Anxiety also decreases people’s willingness to engage in social and political activity.

We argue that the relationship between socio-ethnic diversity and political participation is not quite as straightforward as the literature currently suggests. Rather than this relationship being one-size-fits-all, we propose that the link between diversity and political participation depends on a person’s values. In particular, we argue that an individuals’ authoritarian predisposition, their preference for group authority and uniformity over individual autonomy and diversity, will influence how they respond to diversity. People with an authoritarian predisposition, who we refer to as authoritarians, tend to have higher than average levels of anxiety, to have a lower than average ability to cope with diversity, and to hold prejudiced and intolerant attitudes toward outsiders as a result. Authoritarians also tend to participate in politics at a relatively low rate.

In high-diversity settings, it seems intuitive that authoritarians will see an incentive to get politically involved in an effort to bring policy in line with their preferences—to reduce diversity. We challenge this intuition, arguing that authoritarians, who live in a fairly constant state of threat and anxiety, are largely unaffected by the threat that accompanies socio-ethnic diversity. Essentially, socio-ethnic diversity will not alarm authoritarians because they are already alarmed. This constant state of anxiety is why authoritarians are less likely to participate to begin with.

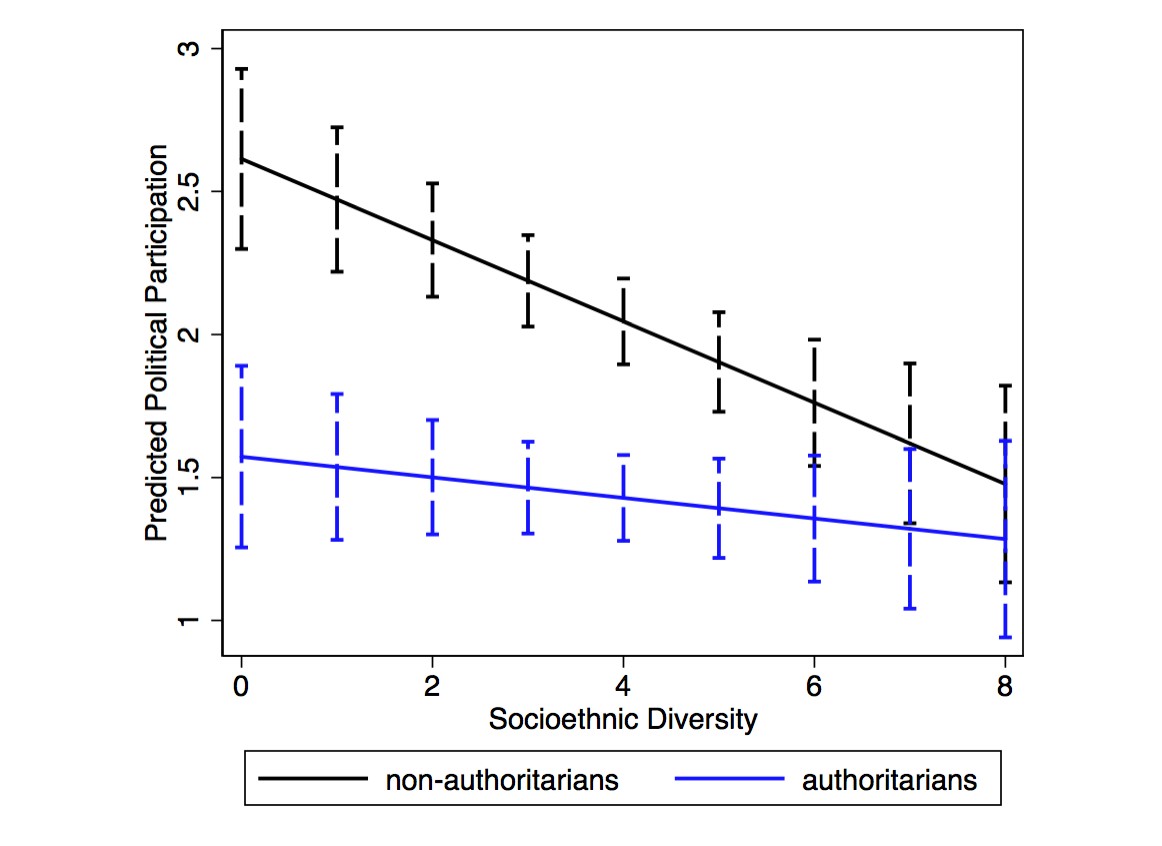

On the other hand, non-authoritarians are less prone to feeling threatened and are therefore normally much less anxious. They are not however, immune to feeling threatened. Nor does their preference for individual autonomy and diversity render them impervious to the anxiety we all feel when confronted with those who seem to be very different from us. Previous research finds that when non-authoritarians do feel threatened, they tend to respond very similarly to authoritarians. We therefore expect that higher levels of socio-ethnic diversity should increase perceived threat among non-authoritarians and thereby lower their levels of political participation. Taken together, the normally low levels of participation among authoritarians and the reduced levels of participation among non-authoritarians should result in a convergence in participation levels across authoritarians and non-authoritarians where society is very diverse.

To test all this, we gather data on people’s political participation, their authoritarian predisposition, and on socio-ethnic diversity from over 50 countries from around the world. We create a measure of political participation that includes signing a petition, joining in boycotts, attending peaceful demonstrations, and membership in a political party. (Our findings are similar when we also consider voter turnout.) We measure authoritarianism using a question that asks people what values they think should be taught to children. Socio-ethnic diversity is measured using a popular scale from Alesina and coauthors.

An example of our findings is provided in the figure. Among authoritarians, there is essentially no relationship between socio-ethnic diversity and political participation. On the other hand, there is a strong and negative relationship between diversity and participation among non-authoritarians. As a result, in countries with high levels of socio-ethnic diversity, predicted levels of participation among authoritarians and non-authoritarians are about the same.

The patterns we uncover help explain recent electoral successes of radical-right parties in Europe and to dispel a commonly held assumption about the potential reasons for this success. The ideas and policies of radical-right parties, which include nativism, stricter immigration policies, nationalism, and belief in a strictly ordered society, are attractive to authoritarians. Thus, with the surge of immigration into European countries mentioned at the outset, it seems reasonable to assume that radical-right parties’ improved election returns stem from an authoritarian backlash against rising socio-ethnic diversity.

However, our examination of political participation rates among authoritarians and non-authoritarians suggests that such an assumption is incorrect. Our findings suggest that the success of radical-right parties is not a result of increased authoritarian participation, but instead a result of the decline in the participation on non-authoritarians. When non-authoritarians participate less and authoritarians continue to participate at the same rate, the politically active portion of the population becomes more authoritarian. Given the more intolerant and punitive policy preferences of authoritarians, this closing gap in participation levels may have a considerable impact on election results and, in turn, the policy preferences of elected representatives.

Shane P. Singh is an associate professor in the School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Georgia. His website is here.

Kris Dunn is a lecturer in comparative politics in the School of Politics and International Studies at the University of Leeds. His website is here.

The article 'Authoritarianism, socioethnic diversity and political participation across countries' (European Journal of Political Research, 54: 563–581), authored by Shane P. Singh and Kris Dunn, is available here.